And now for something completely different

Table of Contents

Starting in 2019, Python 3.8 and 3.9 release manager Łukasz Langa added a new section to the release notes called “And now for something completely different” with a sketch transcript from Monty Python.

For Python 3.10 and 3.11, the next release manager Pablo Galindo Salgado continued the section but included astrophysics facts.

For Python 3.12, the next RM Thomas Wouters shared poems (and took a break for 3.13).

And for Python 3.14, I’m doing all things π, pie and [mag]pie.

Here’s a collection of my different things for the first year (and a bit) of Python 3.14.

alpha 1 #

π (or pi) is a mathematical constant, approximately 3.14, for the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It is an irrational number, which means it cannot be written as a simple fraction of two integers. When written as a decimal, its digits go on forever without ever repeating a pattern.

Here’s 76 digits of π:

3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197169399375105820974944592307816406286

Piphilology is the creation of mnemonics to help remember digits of π.

In a pi-poem, or “piem”, the number of letters in a word equal the corresponding digit. This covers 9 digits, 3.14159265:

How I wish I could recollect pi easily today!

One of the most well-known covers 15 digits, 3.14159265358979:

How I want a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy chapters involving quantum mechanics!

Here’s a 35-word piem in the shape of a circle, 3.1415926535897932384626433832795728:

It’s a fact A ratio immutable Of circle round and width, Produces geometry’s deepest conundrum. For as the numerals stay random, No repeat lets out its presence, Yet it forever stretches forth. Nothing to eternity.

The Guinness World Record for memorising the most digits is held by Rajveer Meena, who recited 70,000 digits blindfold in 2015. The unofficial record is held by Akira Haraguchi who recited 100,000 digits in 2006.

alpha 2 #

Ludolph van Ceulen (1540-1610) was a fencing and mathematics teacher in Leiden, Netherlands, and spent around 25 years calculating π (or pi), using essentially the same methods Archimedes employed some seventeen hundred years earlier.

Archimedes estimated π by calculating the circumferences of polygons that fit just inside and outside of a circle, reasoning the circumference of the circle lies between these two values. Archimedes went up to polygons with 96 sides, for a value between 3.1408 and 3.1428, which is accurate to two decimal places.

Van Ceulen used a polygon with half a billion sides. He published a 20-decimal value in his 1596 book Vanden Circkel (“On the Circle”), and later expanded it to 35 decimals:

3.14159265358979323846264338327950288

Van Ceulen’s 20 digits is more than enough precision for any conceivable practical purpose. For example, even if a printed circle was perfect down to the atomic scale, the thermal vibrations of the molecules of ink would make most of those digits physically meaningless. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s highest accuracy calculations, for interplanetary navigation, uses 15 decimals: 3.141592653589793.

At Van Ceulen’s request, his upper and lower bounds for π were engraved on his tombstone in Leiden. The tombstone was eventually lost but restored in 2000. In the Netherlands and Germany, π is sometimes referred to as the “Ludolphine number”, after Van Ceulen.

alpha 3 #

A mince pie is a small, round covered tart filled with “mincemeat”, usually eaten during the Christmas season – the UK consumes some 800 million each Christmas. Mincemeat is a mixture of things like apple, dried fruits, candied peel and spices, and originally would have contained meat chopped small, but rarely nowadays. They are often served warm with brandy butter.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest mention of Christmas mince pies is by Thomas Dekker, writing in the aftermath of the 1603 London plague, in Newes from Graues-end: Sent to Nobody (1604):

Ten thousand in London swore to feast their neighbors with nothing but plum-porredge, and mince-pyes all Christmas.

Here’s a meaty recipe from Rare and Excellent Receipts, Experienc’d and Taught by Mrs Mary Tillinghast and now Printed for the Use of her Scholars Only (1678):

XV. How to make Mince-pies.

To every pound of Meat, take two pound of beef Suet, a pound of Corrants, and a quarter of an Ounce of Cinnamon, one Nutmeg, a little beaten Mace, some beaten Colves, a little Sack & Rose-water, two large Pippins, some Orange and Lemon peel cut very thin, and shred very small, a few beaten Carraway-seeds, if you love them the Juyce of half a Lemon squez’d into this quantity of meat; for Sugar, sweeten it to your relish; then mix all these together and fill your Pie. The best meat for Pies is Neats-Tongues, or a leg of Veal; you may make them of a leg of Mutton if you please; the meat must be parboyl’d if you do not spend it presently; but if it be for present use, you may do it raw, and the Pies will be the better.

alpha 4 #

In Python, you can use Greek letters as constants. For example:

from math import pi as π

def circumference(radius: float) -> float:

return 2 * π * radius

print(circumference(6378.137)) # 40075.016685578485

alpha 5 #

2025-01-29 marked the start of a new lunar year, the Year of the Snake 🐍 (and the Year of Python?).

For centuries, π was often approximated as 3 in China. Some time between the years 1 and 5 CE, astronomer, librarian, mathematician and politician Liu Xin (劉歆) calculated π as 3.154.

Around 130 CE, mathematician, astronomer, and geographer Zhang Heng (張衡, 78–139) compared the celestial circle with the diameter of the earth as 736:232 to get 3.1724. He also came up with a formula for the ratio between a cube and inscribed sphere as 8:5, implying the ratio of a square’s area to an inscribed circle is √8:√5. From this, he calculated π as √10 (~3.162).

Third century mathematician Liu Hui (刘徽) came up with an algorithm for calculating π iteratively: calculate the area of a polygon inscribed in a circle, then as the number of sides of the polygon is increased, the area becomes closer to that of the circle, from which you can approximate π.

This algorithm is similar to the method used by Archimedes in the 3rd century BCE and Ludolph van Ceulen in the 16th century CE (see 3.14.0a2 release notes), but Archimedes only went up to a 96-sided polygon (96-gon). Liu Hui went up to a 192-gon to approximate π as 157/50 (3.14) and later a 3072-gon for 3.14159.

Liu Hu wrote a commentary on the book The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art which included his π approximations.

In the fifth century, astronomer, inventor, mathematician, politician, and writer Zu Chongzhi (祖沖之, 429–500) used Liu Hui’s algorithm to inscribe a 12,288-gon to compute π between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927, correct to seven decimal places. This was more accurate than Hellenistic calculations and wouldn’t be improved upon for 900 years.

Happy Year of the Snake!

alpha 6 #

March 14 is celebrated as pi day, because 3.14 is an approximation of π. The day is observed by eating pies (savoury and/or sweet) and celebrating π. The first pi day was organised by physicist and tinkerer Larry Shaw of the San Francisco Exploratorium in 1988. It is also the International Day of Mathematics and Albert Einstein’s birthday. Let’s all eat some pie, recite some π, install and test some py, and wish a happy birthday to Albert, Loren and all the other pi day children!

alpha 7 #

On Saturday, 5th April, 3.141592653589793 months of the year had elapsed.

beta 1 #

The mathematical constant pi is represented by the Greek letter π and represents the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. The first person to use π as a symbol for this ratio was Welsh self-taught mathematician William Jones in 1706. He was a farmer’s son born in Llanfihangel Tre’r Beirdd on Angelsy (Ynys Môn) in 1675 and only received a basic education at a local charity school. However, the owner of his parents’ farm noticed his mathematical ability and arranged for him to move to London to work in a bank.

By age 20, he served at sea in the Royal Navy, teaching sailors mathematics and helping with the ship’s navigation. On return to London seven years later, he became a maths teacher in coffee houses and a private tutor. In 1706, Jones published Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos which used the symbol π for the ratio of a circle’s circumference to diameter (hunt for it on pages 243 and 263 or here). Jones was also the first person to realise π is an irrational number, meaning it can be written as decimal number that goes on forever, but cannot be written as a fraction of two integers.

But why π? It’s thought Jones used the Greek letter π because it’s the first letter in perimetron or perimeter. Jones was the first to use π as our familiar ratio but wasn’t the first to use it in as part of the ratio. William Oughtred, in his 1631 Clavis Mathematicae (The Key of Mathematics), used π/δ to represent what we now call pi. His π was the circumference, not the ratio of circumference to diameter. James Gregory, in his 1668 Geometriae Pars Universalis (The Universal Part of Geometry) used π/ρ instead, where ρ is the radius, making the ratio 6.28… or τ. After Jones, Leonhard Euler had used π for 6.28…, and also p for 3.14…, before settling on and popularising π for the famous ratio.

beta 2 #

In 1897, the State of Indiana almost passed a bill defining π as 3.2.

Of course, it’s not that simple.

Edwin J. Goodwin, M.D., claimed to have come up with a solution to an ancient geometrical problem called squaring the circle, first proposed in Greek mathematics. It involves trying to draw a circle and a square with the same area, using only a compass and a straight edge. It turns out to be impossible because π is transcendental (and this had been proved just 13 years earlier by Ferdinand von Lindemann), but Goodwin fudged things so the value of π was 3.2 (his writings have included at least nine different values of π: including 4, 3.236, 3.232, 3.2325… and even 9.2376…).

Goodwin had copyrighted his proof and offered it to the State of Indiana to use in their educational textbooks without paying royalties, provided they endorsed it. And so Indiana Bill No. 246 was introduced to the House on 18th January 1897. It was not understood and initially referred to the House Committee on Canals, also called the Committee on Swamp Lands. They then referred it to the Committee on Education, who duly recommended on 2nd February that “said bill do pass”. It passed its second reading on the 5th and the education chair moved that they suspend the constitutional rule that required bills to be read on three separate days. This passed 72-0, and the bill itself passed 67-0.

The bill was referred to the Senate on 10th February, had its first reading on the 11th, and was referred to the Committee on Temperance, whose chair on the 12th recommended “that said bill do pass”.

A mathematics professor, Clarence Abiathar Waldo, happened to be in the State Capitol on the day the House passed the bill and walked in during the debate to hear an ex-teacher argue:

The case is perfectly simple. If we pass this bill which establishes a new and correct value for pi , the author offers to our state without cost the use of his discovery and its free publication in our school text books, while everyone else must pay him a royalty.

Waldo ensured the senators were “properly coached”; and on the 12th, during the second reading, after an unsuccessful attempt to amend the bill it was postponed indefinitely. But not before the senators had some fun.

The Indiana News reported on the 13th:

…the bill was brought up and made fun of. The Senators made bad puns about it, ridiculed it and laughed over it. The fun lasted half an hour. Senator Hubbell said that it was not meet for the Senate, which was costing the State $250 a day, to waste its time in such frivolity. He said that in reading the leading newspapers of Chicago and the East, he found that the Indiana State Legislature had laid itself open to ridicule by the action already taken on the bill. He thought consideration of such a proposition was not dignified or worthy of the Senate. He moved the indefinite postponement of the bill, and the motion carried.

beta 3 #

If you’re heading out to sea, remember the Maritime Approximation:

π mph = e knots

beta 4 #

All this talk of π and yet some say π is wrong. Tau Day (June 28th, 6/28 in the US) celebrates τ as the “true circle constant”, as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its radius, C/r = 6.283185… The Tau Manifesto declares π “a confusing and unnatural choice for the circle constant”, in part because “2π occurs with astonishing frequency throughout mathematics”.

If you wish to embrace τ the good news is PEP 628

added math.tau to Python 3.6

in 2016:

When working with radians, it is trivial to convert any given fraction of a circle to a value in radians in terms of

tau. A quarter circle istau/4, a half circle istau/2, seven 25ths is7*tau/25, etc. In contrast with the equivalent expressions in terms ofpi(pi/2,pi,14*pi/25), the unnecessary and needlessly confusing multiplication by two is gone.

release candidate 1 #

Today, 22nd July, is Pi Approximation Day, because 22/7 is a common approximation of π and closer to π than 3.14.

22/7 is a Diophantine approximation, named after Diophantus of Alexandria (3rd century CE), which is a way of estimating a real number as a ratio of two integers. 22/7 has been known since antiquity; Archimedes (3rd century BCE) wrote the first known proof that 22/7 overestimates π by comparing 96-sided polygons to the circle it circumscribes.

Another approximation is 355/113. In Chinese mathematics, 22/7 and 355/113 are respectively known as Yuelü (约率; yuēlǜ; “approximate ratio”) and Milü (密率; mìlǜ; “close ratio”).

Happy Pi Approximation Day!

release candidate 2 #

The magpie, Pica pica in Latin, is a black and white bird in the crow family, known for its chattering call.

The first-known use in English is from a 1589 poem, where magpie is spelled “magpy” and cuckoo is “cookow”:

Th[e]y fly to wood like breeding hauke, And leave old neighbours loue, They pearch themselves in syluane lodge, And soare in th’ aire aboue. There : magpy teacheth them to chat, And cookow soone doth hit them pat.

The name comes from Mag, short for Margery or Margaret (compare robin redbreast, jenny wren, and its corvid relative jackdaw); and pie, a magpie or other bird with black and white (or pied) plumage. The sea-pie (1552) is the oystercatcher, the grey pie (1678) and murdering pie (1688) is the great grey shrike. Others birds include the yellow and black pie, red-billed pie, wandering tree-pie, and river pie. The rain-pie, wood-pie and French pie are woodpeckers.

Pie on its own dates to before 1225, and comes from the Latin name for the bird, pica.

release candidate 3 #

According to Pablo Galindo Salgado at PyCon Greece:

There are things that are supercool indeed, like for instance, this is one of the results that I’m more proud about. This equation over here, which you don’t need to understand, you don’t need to be scared about, but this equation here tells what is the maximum time that it takes for a ray of light to fall into a black hole. And as you can see the math is quite complicated but the answer is quite simple: it’s 2π times the mass of the black hole. So if you normalise by the mass of the black hole, the answer is 2π. And because there is nothing specific about your election of things in this formula, this formula is universal. It means it doesn’t depend on anything other than nature itself. Which means that you can use this as a definition of π. This is a valid alternative definition of the number π. It’s literally half the maximum time it takes to fall into a black hole, which is kind of crazy. So next time someone asks you what π means you can just drop this thing and impress them quite a lot. Maybe Hugo could use this information to put it into the release notes of πthon [yes, I can, thank you!].

3.14.0 (final) #

Edgar Allen Poe died on 7th October 1849.

As we all recall from 3.14.0a1, piphilology is the creation of mnemonics to help memorise the digits of π, and the number of letters in each word in a pi-poem (or “piem”) successively correspond to the digits of π.

In 1995, Mike Keith, an American mathematician and author of constrained writing, retold Poe’s The Raven as a 740-word piem. Here’s the first two stanzas of Near A Raven:

Poe, E. Near a Raven

Midnights so dreary, tired and weary. Silently pondering volumes extolling all by-now obsolete lore. During my rather long nap - the weirdest tap! An ominous vibrating sound disturbing my chamber’s antedoor. “This”, I whispered quietly, “I ignore”.

Perfectly, the intellect remembers: the ghostly fires, a glittering ember. Inflamed by lightning’s outbursts, windows cast penumbras upon this floor. Sorrowful, as one mistreated, unhappy thoughts I heeded: That inimitable lesson in elegance - Lenore - Is delighting, exciting…nevermore.

3.14.1 #

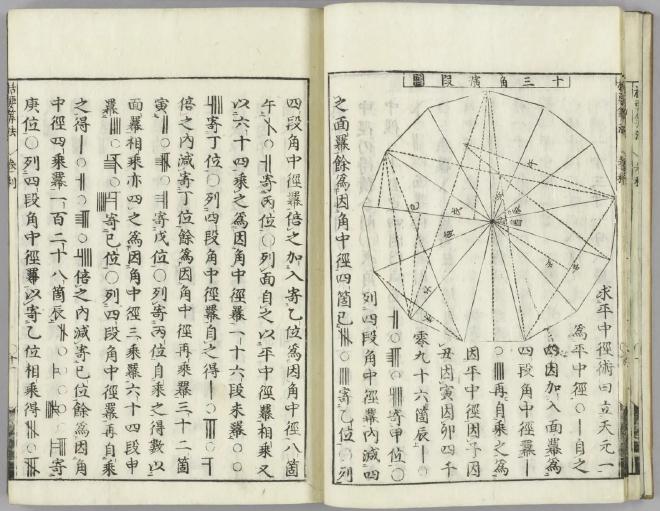

Seki Takakazu (関 孝和; c. March 1642 – December 5, 1708) was a Japanese mathematician and samurai who laid the foundations of Japanese mathematics, later known as wasan (和算, from wa (“Japanese”) and san (“calculation”).

Seki was a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz but worked independently. He created a new algebraic system, worked on infinitesimal calculus, and is credited with the discovery of Bernoulli numbers (before Bernoulli’s birth).

Seki also calculated π to 11 decimal places using a polygon with 131,072 sides inscribed within a circle, using an acceleration method now known as Aitken’s delta-squared process, which was rediscovered by Alexander Aitken in 1926.

Header photo: A scan of Seki Takakazu’s posthumous Katsuyō Sanpō (1712) showing calculations of π.